Deep Dive: Understanding the Time Value of Money in Commercial Real Estate

In commercial real estate, nearly every investment decision boils down to a key question: What is the present value of uncertain future cash flows? The answer exists because money has a fundamental property: its value changes over time.

The time value of money (TVM) rests on a simple premise: a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow because it can be invested, is subject to inflation, and faces uncertainty about future realization. This definition is at the heart of the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuation.

But the time value of money isn’t just a formula. In practice, it is interpreted in two complementary ways:

- From the investor: as an expression of time preference + opportunity cost + risk aversion (your “minimum rate of return”).

- From the market: as the price of capital (base rates, spreads, liquidity and risk appetite) that ends up “encoded” in prices, capitalization rates and required returns.

The real estate analyst’s job is to make these two visions converse within the financial model.

Economic intuition: why money “shrinks” into the future

Imagine two identical promises:

- Get $1 Today

- Receive $1 within 5 years

Even without considering risk, a dollar today holds more value because it can be invested to earn returns. If, in addition, we consider inflation (loss of purchasing power) and risk (uncertainty), the value of that future dollar is reduced even more.

This is why, in commercial real estate, it’s not enough to simply sum expected cash flows; you must discount them to determine their present value.

The Math Behind TVM: Capitalization and Discount

The time value of money has two core components: capitalization (projecting future value) and discounting (calculating present value).

a) Future Value: carrying money from today to tomorrow

If you have a present value today and it grows at a rate over a period:

FV = PV × (1 + r)^n

b) Present Value: bringing future money to the present

If you expect to receive future value in periods:

PV = FV / (1 + r)^n

c) Discount of a flow (DCF): the “engine” of real estate analysis

If an asset generates a flow in the period, its value today (for that flow) is:

PVt = CFt / (1 + r)^t

And the total present value of all expected flows is:

NPV = Σ [CFt / (1 + r)^t] − CF0

Where the initial investment is usually (e.g., the purchase price, plus closing costs, and cap rate initial).

What is “r”?

The discount rate is a meeting point between the investor and the market

In a discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, “r” represents the discount rate, the annual return used to convert future cash flows into present value, reflecting both opportunity cost and risk. In other words, it is the “ruler” with which the investor measures whether a future flow “compensates” today.

In summary, the discount rate (r) reflects risk and opportunity cost, and represents the target return that an investor demands given the uncertainty profile of those cash flows. In theory, it is “only” a number, in practice, it is an investment hypothesis.

The important thing (and what usually confuses) is that r ”does not come” from the property. The property produces (or does not) certain inflows and outflows of cash; The discount rate is an “input” or piece of information that the investor brings to the table.

Investor’s point of view: “my required rate”

The most practical way to understand the discount rate is as a function of:

- Returns expected by the investor

- Returns available in comparable alternatives

This set of alternatives usually follows a staggered logic:

UST “near-free risk” → corporate bonds (credit risk) → equity (residual risk). Your “r” aligns with that opportunity set: if the market pays me X for a more liquid and/or less risky instrument, how much more do I need to accept the risk and illiquidity of this real estate asset?

In contrast, variables such as real estate prices or fiscal friction can affect the level and form of flows (growth, NOI, resale, after-tax cash flows), but they should not be the primary anchor of the discount rate. These factors are modeled within the DCF, in the numerator, while r is the “price of capital” and risk, in the denominator.

What return do I need to prefer this asset over other alternatives?

That alternative can be:

- A comparable portfolio

- Debt (if your capital competes with originating/prioritizing loans)

- Another deal with a different risk

- A liquid instrument (bonds, stock market, etc.)

That’s why A.CRE often connects time value of money to metrics like IRR (the rate that makes NPV zero), because IRR synthesizes the time value of money that we applied to the entire investment.

Market view: “the price of capital”

Understood the basic point in our discount rate – r ≈ risk-free rate + spreads for relevant risks

The market “votes” daily with:

- Risk-free rates (sovereign curves)

- Credit spreads

- Liquidity (how easy it is to get in/out)

- Risk sentiment

In CRE, this price of capital is filtered towards:

- Financing rates (cost of debt)

- Capitalization rates (implied return)

- Discounts required (especially on less liquid assets or with higher operational risk)

Then come premiums, which in real estate typically capture:

- Illiquidity (you can’t sell tomorrow at the “market price” of a stock)

- Operational risk (occupancy, tenant credit, costs, capitalization)

- Market risk (absorption, new supply, regulatory, cycle)

- Execution risk (whether value-add or opportunistic)

At the institutional level, the discount rate typically starts with the investor’s average cost of capital and then adjusts for asset-specific risks, strategy (core, value-add, opportunistic), and market conditions.

In conclusion: Market vs investor: who “places” r and who “defines” the price?

Here’s the “meeting point”:

- The market suggests a range of required returns (by base rates, spreads, liquidity, risk appetite).

- The investor defines their final discount rate based on:

- Cost of capital,

- Real set of alternatives,

- Risk tolerance,

- and its strategy.

In liquid and highly competitive markets, many buyers end up converging to similar ranges; But the discount rate is still, technically, an input from the investor or analyst.

The discount rate is not an “asset truth”; it is a “truth of capital”.

To explore more about the IRR vs discount rates relationship, I recommend reading our article: IRR vs Discount Rate: Two Sides of the Same Coin (Case Study + Model)

How time value of money drives Commercial Real Estate valuations

When Perspective Shapes Value

Whenever we talk about real estate investments, we address the fact that “every property or project is unique,” but we rarely hear anyone say, “This investor is truly one of a kind.” The appreciation (and valuation) of a project or property can change dramatically depending on its location, type, or strategy, but also from the perspective of those who view it as an investment.

The time value of money helps explain why the same property can have different values depending on who is looking at it. From an appraisal standpoint, value is often estimated using a stabilized NOI and a market cap rate to determine what the property might trade for today.

This approach captures market conditions at a point in time, but it does not explicitly show when future cash flows are received. From an investor’s perspective, however, valuation is forward-looking: all expected cash flows, operating income, capital expenditures, and the eventual sale, are discounted back to today using a required rate of return.

This is where the time value of money becomes central, because cash received sooner is worth more than cash received later.

Timing it is implicit in Investment Strategy

This distinction also helps clarify the difference between investment strategies. For example, core assets tend to produce stable, predictable cash flows early in the investment period, which means less discounting and lower required returns.

Value-Add assets, on the other hand, often push a larger portion of their value into later years through lease-up, renovations, or repositioning. Because those future cash flows are both delayed and riskier, investors typically apply a higher discount rate, which reduces the present value unless the upside is meaningful enough to compensate for the time and risk involved.

The concept vs Practical application

So, once you understand the concept, the natural question becomes: how do you bring an abstract idea like the time value of money into daily practice? As Spencer often reminds us, this is exactly where a good analyst earns their paycheck.

If you already understand the mechanics behind the analysis and have gathered as much information as possible about the investor profile, the market, your role, the team, and the property itself, the next step is to apply judgment and creativity. At this stage, the goal is to use the full set of available tools to produce a robust and thoughtful financial analysis, one that reflects a more complete view of the investment opportunity and helps reduce friction and uncertainty in decision-making.

A clear example of this mindset comes directly from Spencer’s own work. Take the equity multiple, a return metric that is widely used across real estate financial analysis. While helpful, Spencer challenged a fundamental question: does it really capture the full picture? When we account for the time value of money, the answer is often no. In response, Spencer introduced the Weighted Equity Multiple, a refinement that explicitly considers the timing of capital inflows and outflows, producing a more accurate representation of how capital is actually deployed and returned over time.

Return metrics like the Weighted Equity Multiple reinforce a key lesson of the time value of money: two investments may deliver the same total multiple of invested capital, but the one that returns capital earlier will almost always be more attractive. Earlier distributions can be reinvested, compounding opportunity value and improving overall capital efficiency.

In CRE valuation, the time value of money ensures that timing matters just as much as magnitude, allowing investors and analysts to compare properties, strategies, and markets on a consistent and economically meaningful basis.

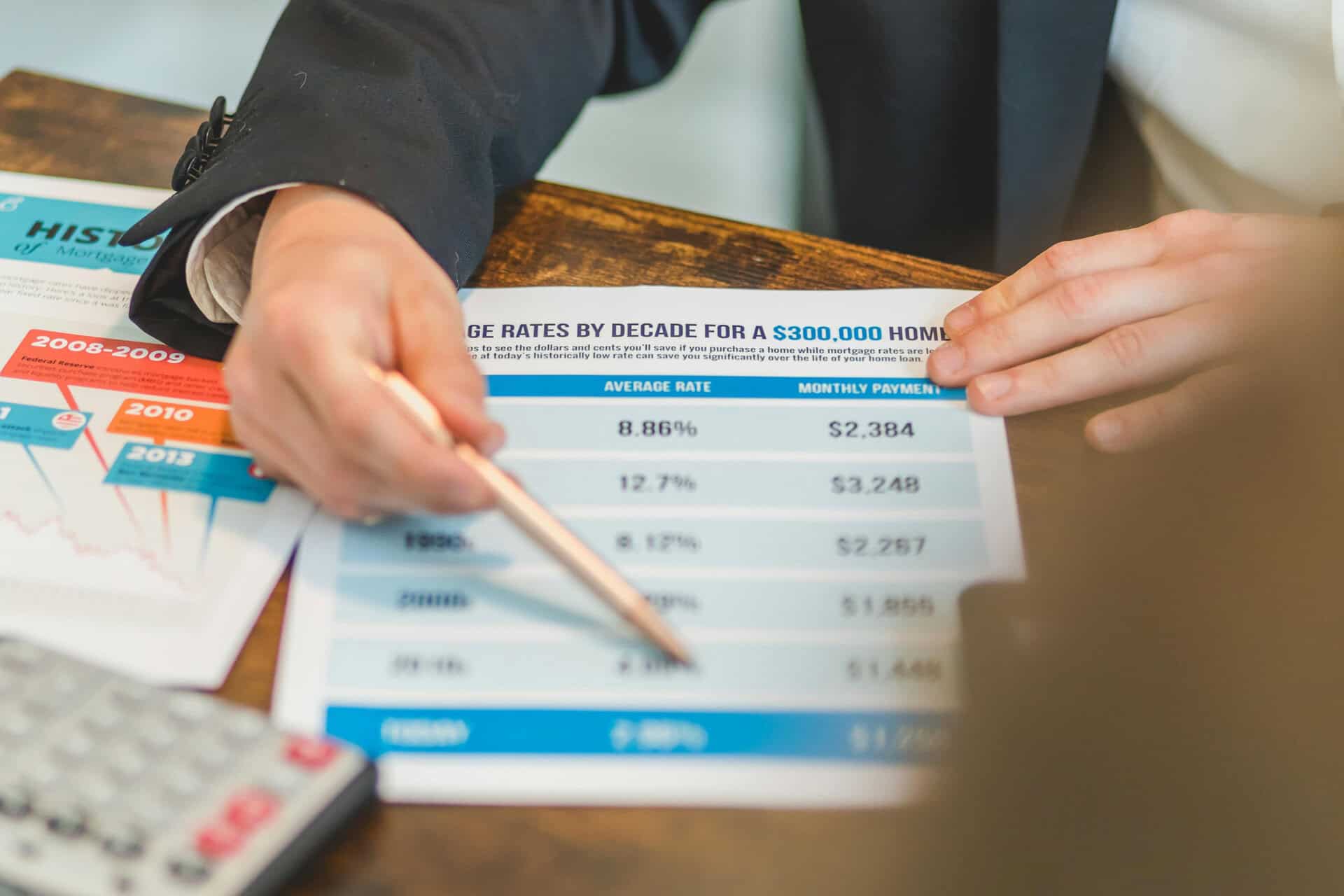

Direct Cap and DCF: Two Lenses on the Same Income Stream

When using an Income Approach, investors and analysts typically triangulate value using both Direct Capitalization and DCF, because each answers the same core question, what is this income stream worth today?, but with different resolutions around timing. Direct cap compresses the story into a clean, fast estimate, but it hinges on two judgments: how you define “stabilized” NOI and what cap rate the market is paying for comparable income streams.

The real professional must value logic inside the assumptions. Getting “the right NOI” is not about copying the trailing twelve months; it requires disciplined normalization, deciding what income and expenses are truly recurring, representative, and consistent with long-term operations. Likewise, selecting a cap rate is not a plug; it’s a market-based decision tested against the broader cost of capital environment. Because small shifts in NOI or cap rate can materially modify value, the quality of a valuation depends less on the formula and more on your ability to source data, adjust for non-recurring items, pressure-test, and defend why your inputs reflect a realistic steady-state view of the property.

Then, the timeline comes into play, our discounted cash flows express the same valuation logic in a time-explicit way. You forecast annual cash flows, including lease-up dynamics, CapEx, and the reversion/sale, and discount each cash flow back to today using a discount rate that reflects the time value of money, risk, and opportunity cost.

The practical point isn’t that one method is “better,” but that using them together forces clarity: direct cap provides a market-anchored snapshot, while DCF makes timing and risk explicit, showing how differences in when cash arrives (and the uncertainty around it) can justify a premium or discount relative to a simple stabilized conclusion.

In a typical acquisition, DCF is not an academic exercise: it is the “dashboard” for connecting operational assumptions with return.

a) DCF in acquisition: price as input, IRR as output

In practice, many models do not “solve” the price with a discount rate; Instead:

- The purchase price is assumed

- The model calculates the resulting IRR

- The analyst can review inputs or metrics such as the purchase price, operating performance, capital expenditures, exit assumptions, or capital structure until the target IRR is reached

This way of working is consistent with how real transactions are negotiated: the price is defined by the market, and the investor decides whether the return “closes” or not.

b) Quick numerical example: how the value changes with the rate

Assume an asset with a holding period of 5 years and projected net flows (without leverage):

- Year 1: 500,000

- Year 2: 550,000

- Year 3: 600,000

- Year 4: 650,000

- Year 5: 700,000 + Net Sale: 10,000,000

If you discount at 8%, the approximate present value of those flows is $9.17M.

If you discount at 12%, it drops to $7.80M.

If you discount at 15%, it drops to $6.94M.

The same asset and the same projected cash flows can yield different fair values depending on the applied discount rate and perception of time and risk.

c) In real estate, the time value of money is not isolated: it depends on the type of flow

It is not the same as “discount”:

- A bond-like lease with institutional-grade tenants.

- An asset with a high risk of tenant renewal, structural vacancy or uncertain capitalization.

- A development (execution risk)

- A hotel (highly cyclical income)

This is where the time value of money ceases to be “mathematical” and becomes a selection criteria and expertise.

Technical consistency: nominal vs real

A golden rule:

- If you project nominal flows (including inflation), use a nominal rate.

- If you project real flows (without inflation), use a real rate.

The classic (approximate) relationship is:

(1 + r_nominal) ≈ (1 + r_real) × (1 + expected inflation)

In markets with low inflation, the difference between real and nominal can seem small. In markets with higher inflation (common in LATAM), inconsistency can affect your conclusion.

Macroeconomics: Why the US, Eurozone and LATAM “discount” differently?

In practice, the Time Value of Money is “discounted” differently between the US, the Eurozone and the LATAM markets because the discount factor ends up absorbing three macro forces that are not homogeneous: (1) the level and volatility of inflation (which erode or stabilize the purchasing power of flows), (2) monetary policy rates (which anchor the marginal cost of money and are passed on to the cost of debt, and to the required returns), and (3) premiums for sovereign risk, exchange rate risk and illiquidity (which raise the required return when macro uncertainty and capital market depth are lower).

The time value of money is expressed through a discount rate, which is influenced by macroeconomic variables that vary across countries and market cycles. Three key channels:

- Inflation (and inflation expectations)

- Monetary Policy Rate / System Base Rates

- Country risk premium, exchange rate risk and liquidity

Here’s a “summary” (latest data available around Dec-2025 / Jan-2026) to see why time value of money doesn’t feel the same in different regions:

- US: CPI inflation 12m 2.7% (Dec-2025).

- Eurozone: Annual inflation (HICP) 2.0% (Dec-2025 estimate).

- Brazil: 2025 cumulative HICP 4.26%.

- Mexico: Inflation (Dec-2024 to Dec-2025) 3.69% (indicator shown by Banxico).

In reference rates:

- US: Fed funds target range 3.50%–3.75%.

- Eurozone: ECB deposit facility rate (DFR) 2.00%.

- Brazil: Selic 15.00% (COPOM).

- Mexico: Overnight target rate 7.00% (Dec 2025).

How does data affect the analysis of a property?

While in the US and the Eurozone the discount is usually more “anchored” to relatively observable and deep benchmarks (inflation measured by statistical agencies and Fed/ECB guidance rates) with spreads that tend to move within narrower ranges, in much of LATAM the greater sensitivity to external shocks, exchange rate volatility and country risk push for higher nominal rates and premiums (or to indexed/dollarized structures) to compensate for uncertainty, which makes a DCF punish more strongly the most distant flows and amplify the importance of assumptions such as real vs. nominal growth and the exit strategy.

Channel 1: Inflation → Nominal Growth in Rents and Costs

- In contracts with fixed scales, unexpected inflation can compress real NOI.

- In indexed contracts, inflation can be passed-on, but with delays, ceilings, or frictions.

- In properties with sensitive operating costs (energy, payroll), inflation can be indexed faster to spending than to income.

Channel 2: Base rates → cost of debt and required return on capital

Higher rates usually involve:

- Higher cost of debt → lower cash flow to capital (and lowers “healthy” leverage).

- Higher discount rate of capital → lower present value.

- Market adjustments in capitalization rates (in many cycles, not always in a 1:1 or immediate way).

Channel 3: country risk premium → “extra” required rate (LATAM)

In LATAM, even with contained inflation, additional bonuses usually appear for:

- Sovereign and regulatory risk

- Convertibility risk/controls

- Exchange rate volatility (when the principal or reference is based on other currencies such as USD)

- Lower exit liquidity

A practical way of thinking about the rate: “building blocks”

Without pretending to be a single recipe, a useful framework is:

- Base rate (in the currency of the analysis)

- Expected inflation premium (if in nominal terms)

- Risk Premiums

- Country

- Liquidity

- Operational risk (vacancy, rollover, CapEx)

- Execution risk (development, repositioning)

In “solid” and liquid markets, the premium block is usually smaller. In less liquid markets or with more volatile macro risk, the block grows, and the time value of money “punishes” the distant projected cash flows more.

A.CRE Checklist: Time Value of Money Discipline into Underwriting

- Consistent currency: If the flows are in local currency, the rate must be in local currency (or you must convert flows to USD with explicit modeling).

- Nominal vs real: define the framework from the beginning and maintain consistency (growth, rate, output).

- Market anchor: Contrast your rate with evidence (available funding, observed market capitalization, spreads).

- Raise awareness of what moves value: discount rate, NOI growth, vacancy/absorption, CapEx.

- Scenarios, not a single number: TVM is very sensitive; an “average” rate can hide asymmetric risk.

- Project spreads judiciously: first, it forecasts (rents, vacancies, macro scenarios), then it decides on the rate and price.

- Forecasting discipline: incorporate our taught practices in our case studies to improve the calibration of your underwriting.

Conclusion

The time value of money is mathematics, but the rate is a thesis.

The Time Value of Money is an elegantly simple tool: discounting to compare alternatives in “today’s dollars.” However, the critical part, and the one that really differentiates a solid analyst, is to understand what the discount rate is where they are:

- Investor preference and restrictions

- The price of money and risk in the market

- The macro reality (inflation, rates, spreads, FX) of the country / real estate market

Mastering these concepts in commercial real estate is ultimately mastering the bridge between forecast, risk, and price.

Recommended Articles

Frequently Asked Questions: Time Value of Money in Commercial Real Estate

What is the time value of money (TVM) in commercial real estate?

The time value of money is the principle that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar received in the future because it can be invested, is affected by inflation, and carries uncertainty. In commercial real estate, TVM underpins valuation methods like discounted cash flow (DCF) by converting future cash flows into today’s dollars.

Why is the time value of money so important for CRE valuation?

Because real estate investments generate cash flows over time, not all at once. TVM ensures that timing matters, allowing investors to compare properties, strategies, and deal structures on a consistent basis by accounting for when cash is received and the risk associated with it.

How does TVM relate to discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis?

DCF is the practical application of the time value of money. Each projected cash flow is discounted back to the present using a discount rate that reflects opportunity cost and risk. The sum of these discounted cash flows represents the asset’s present value.

What does the discount rate (r) represent in a DCF?

The discount rate represents the investor’s required rate of return, combining time preference, opportunity cost, and risk. It is not produced by the property itself; it is an input defined by the investor based on capital market alternatives and risk tolerance.

How do investors and markets differ in how they view the discount rate?

Markets suggest a range of returns through base rates, spreads, and liquidity conditions. Investors then select a specific discount rate based on their cost of capital, strategy, and risk tolerance. The final rate is a meeting point between market pricing and investor judgment.

How does the time value of money explain differences between core and value-add strategies?

Core assets generate cash flows earlier and with more stability, so less discounting is required and returns are lower. Value-add assets push more value into the future through lease-up or repositioning, which increases risk and delay, leading investors to apply higher discount rates.

What is the relationship between cap rates and the time value of money?

Cap rates are a simplified, market-based expression of the time value of money applied to a stabilized income stream. They reflect prevailing discount rates, growth expectations, and risk, but they do not explicitly show the timing of future cash flows the way a DCF does.

Why can the same property have different values for different investors?

Different investors have different required returns, capital constraints, and opportunity sets. Because valuation depends on discounting future cash flows, changes in the perceived time value of money can lead to materially different values for the same asset.

How does inflation affect the time value of money in CRE models?

Inflation erodes purchasing power, so future cash flows are worth less in real terms. Analysts must be consistent: nominal cash flows should be discounted with nominal rates, and real cash flows with real rates. Inconsistent treatment can materially distort valuation.

Why does TVM differ across regions like the US, Europe, and LATAM?

Differences in inflation volatility, base interest rates, country risk, currency stability, and liquidity all affect discount rates. Higher macro uncertainty increases required returns, which penalizes distant cash flows more heavily in a DCF.

How does TVM connect to return metrics like IRR and equity multiple?

IRR is the discount rate that sets a project’s net present value to zero, directly embedding the time value of money. Metrics like the Weighted Equity Multiple further refine this by explicitly accounting for when capital is returned, not just how much.

What is the key takeaway for CRE analysts applying TVM?

The time value of money is simple in concept but powerful in practice. Mastery comes from understanding not just the math, but how discount rates reflect investor preferences, market pricing of risk, and macroeconomic realities—turning forecasts into defensible valuations.