Real Estate Tokenization, Part II: From Concept to Execution

In Part I of this series, we unpacked the basic idea of tokenizing commercial real estate: what it is, why it matters, and where hype often exceeds reality.

In this second part, we move from concept to implementation:

- How commercial property gets tokenized

- Which companies are building the infrastructure for tokenized RWAs and real estate

- How regulation and liquidity really work in practice

Plus: economics, governance, technology choices, a Latin America lens, and practical checklists for sponsors and investors.

*This article is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be interpreted as investment advice, financial guidance, or a solicitation to invest in any asset, token, or platform. A.CRE is not a registered investment advisor and does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee any specific investment product or strategy. Readers should perform their own independent due diligence and, when appropriate, consult with qualified legal, tax, and investment professionals before making any financial decisions. Do your own research.

Tokenization is no longer purely theoretical in capital markets. BlackRock’s BUIDL fund, a tokenized money‑market fund, has surpassed US$1 billion in AUM and now represents a large share of all tokenized treasuries globally.

At the same time, Deloitte projects that tokenized real estate on blockchain networks could exceed US$4 trillion by 2035, up from under US$300 billion in 2024.

Against that backdrop, the core question for real estate professionals is less “Is tokenization real?” and more “If and when does it make sense for my capital stack, in my jurisdiction, for my investor base?”

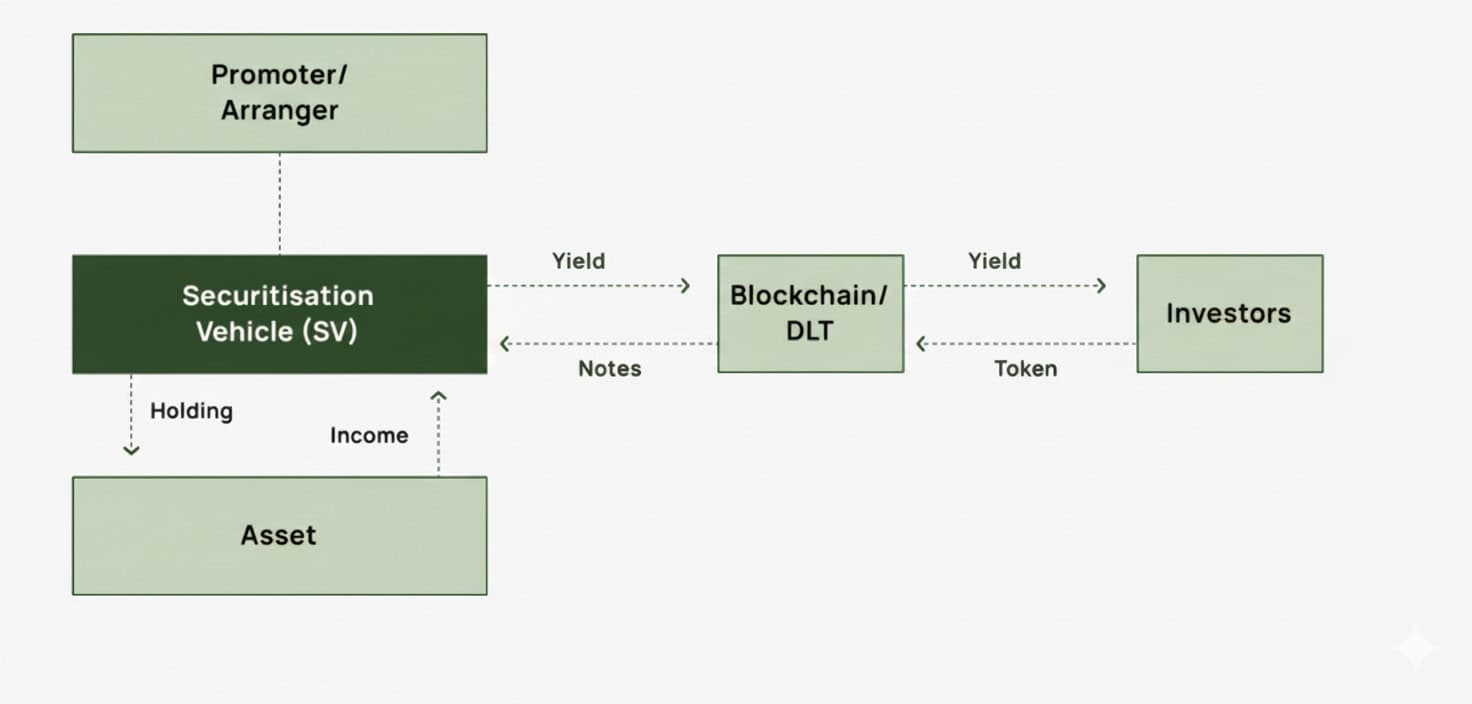

Based on Luxembourg Securitisation. Tokenization. https://luxembourg-securitisation.com/securities/tokenization/

From Building to Blockchain: Tokenization of a CRE Asset

Think of tokenization as a structuring and distribution strategy layered on top of the traditional property, not a completely new asset. The building remains in the land registry; what changes is how claims on its cash flow and value are packaged and traded.

Define the use case and asset

Start with basic underwriting questions:

- Asset type and business plan

- Stabilized vs. value‑add

- Single asset vs. portfolio / fund

- Equity, preferred equity, mezzanine, senior notes, or revenue‑share

- Objective of tokenization

- Lower minimums and broaden investor base

- Make secondary liquidity possible (not guaranteed)

- Speed up fundraising and automate operations (distributions, reporting)

- Investor segment

- Purely institutional, accredited individuals, or retail in specific jurisdictions

These choices will drive your legal structure, regulatory route, and technology stack.

Choose legal structure and jurisdiction

In today’s market, most tokenized real estate deals are structured around an SPV, (Special Purpose Vehicle), an independent legal entity created for a specific purpose, such as isolating financial risks or managing investments.

- An SPV (LLC, S.A., S.à r.l., etc.) holds legal title to the property.

- Tokens represent shares, membership interests, or contractual rights in that SPV (or in a fund that owns multiple SPVs).

Key decisions:

- Where is the property? Local property law may restrict foreign ownership or limit how beneficial interests can be structured.

- Where are your investors? You may rely on U.S. exemptions (Reg D, Reg S, Reg A+), EU/MiCA‑aligned regimes, Dubai’s VARA framework, or local securities laws in Latin America.

- Onshore vs. offshore holding company Some issuers use Luxembourg, Liechtenstein or Cayman structures for cross‑border investors, but that does not exempt them from securities regulation where investors reside.

Decide the regulatory route and offering design

The core legal question: Is the token a security?

If investors are passive and expect profit from the efforts of a sponsor or manager, regulators will almost always treat the token as a security, regardless of the technology used. This is exactly how the U.S. SEC’s digital asset framework applies the Howey test, and why recent SEC statements explicitly stress that tokenized securities are still securities.

Examples:

- United States: Exempt offerings under Reg D (accredited investors), Reg S (offshore investors), and in some cases Reg A+ or Reg CF for broader distribution.

- European Union: Tokenized real estate is usually treated as a traditional financial instrument under existing securities law; MiCA brings clarity around crypto asset providers and stablecoins and influences how platforms are licensed and supervised.

- Dubai / UAE: VARA’s updated rulebook sets out explicit requirements for real‑world asset (RWA) tokenization and secondary trading, creating one of the most detailed frameworks for asset‑backed tokens.

Across jurisdictions, you also need:

- KYC/AML policies

- Clear investor eligibility (e.g., accredited vs. retail)

- Transfer restrictions (lock‑ups, geography, whitelisting of wallets)

Structure economics and valuation

Next, you align the economic rights of the token with your capital stack:

- Valuation and capital stack: Property appraisal, NOI projections, leverage assumptions, DSCR, target IRR.

- What does one token represent? Common equity, preferred equity, subordinated notes, revenue‑share or a hybrid.

- Token economics: Number of tokens, nominal value (e.g., 1,000,000 tokens at US$10 each), target yield, distribution frequency, fees, sponsor promote/waterfall, and any buy‑back or redemption features.

Select the technology stack

At a high level you need:

- Blockchain and token standard

- Most RWA projects use EVM‑compatible chains (Ethereum, Polygon, etc.).

- Security‑token standards like ERC‑1400 and ERC‑3643 embed compliance and transfer restrictions at the token level.

- Compliance layer

- KYC provider, accreditation checks, wallet whitelisting, and logic to enforce lockups and geography constraints.

- Custody and wallets

- Retail‑friendly custodial wallets vs. institutional‑grade custodians.

- Payments

- Fiat wires, cards, and/or stablecoins, depending on your investor base.

Most sponsors won’t build this from scratch; they will plug into a white‑label platform like DigiShares, Blocksquare, or similar solutions that already bundle issuance, KYC, and investor dashboards.

Draft legal documentation and smart contracts

Two tracks run in parallel:

- Off‑chain legal documentation

- Offering memorandum / PPM

- Subscription agreement and shareholder (or noteholder) agreement

- Property management and asset‑management contracts

- Terms and conditions of the token

- On‑chain logic (smart contracts)

- Minting/burning tokens

- Transfer rules and whitelists

- Automated distributions (rents, interest, return of capital)

- Optional voting or governance modules: Importantly, even where votes happen via tokens, corporate records still need to reflect those decisions for them to be enforceable under corporate and property law.

Onboard investors and execute the primary issuance

The issuance process tends to look like a digitized private placement:

- Investor signs up on the platform and passes KYC/AML.

- If required, their accreditation status is verified.

- A blockchain wallet (custodial or self‑custodial) is whitelisted.

- Investor signs subscription documents (digitally).

- Investor funds the subscription (fiat or stablecoin).

- Once funds clear, tokens are minted and sent to the investor’s wallet.

The platform’s register must stay synchronized with the SPV’s legally recognized shareholder or note register.

Run ongoing operations and reporting

After closing, tokenization is mainly an operations and reporting play:

- Cash flow – rents or interest received by the SPV are aggregated, then distributed pro‑rata via smart contract or through the platform’s corporate action tools.

- Investor reporting – periodic financials, occupancy, DSCR, updated valuations, and distribution histories.

- Governance – token‑weighted votes on key decisions (refinance, sale, major capex), reflected in formal resolutions.

Enable secondary trading and design for liquidity

Once any regulatory lock‑up periods expire, you can enable secondary trading:

- Venues: Security tokens usually trade on regulated ATS/MTF‑type platforms, not permissionless DEXes, because they are treated as traditional securities.

- Mechanisms: Order book exchanges, bulletin boards, or periodic auctions; sometimes supplemented by market‑makers or issuer buy‑back programs.

- Restrictions: Transfers only between whitelisted wallets, jurisdictional filters, minimum holding periods.

Exit and unwinding

At the end of the business plan:

- The underlying property or portfolio is sold or refinanced.

- Proceeds flow into the SPV and are allocated via the agreed waterfall (debt, then equity, then promotion).

- Tokens are redeemed and burned or rolled into a new vehicle if investors choose to reinvest.

From an operational perspective, tokenization can simplify this process (especially communication and payments), but the legal and tax consequences are still those of a conventional exit.

Real World Asset and Real Estate Tokenization Platforms

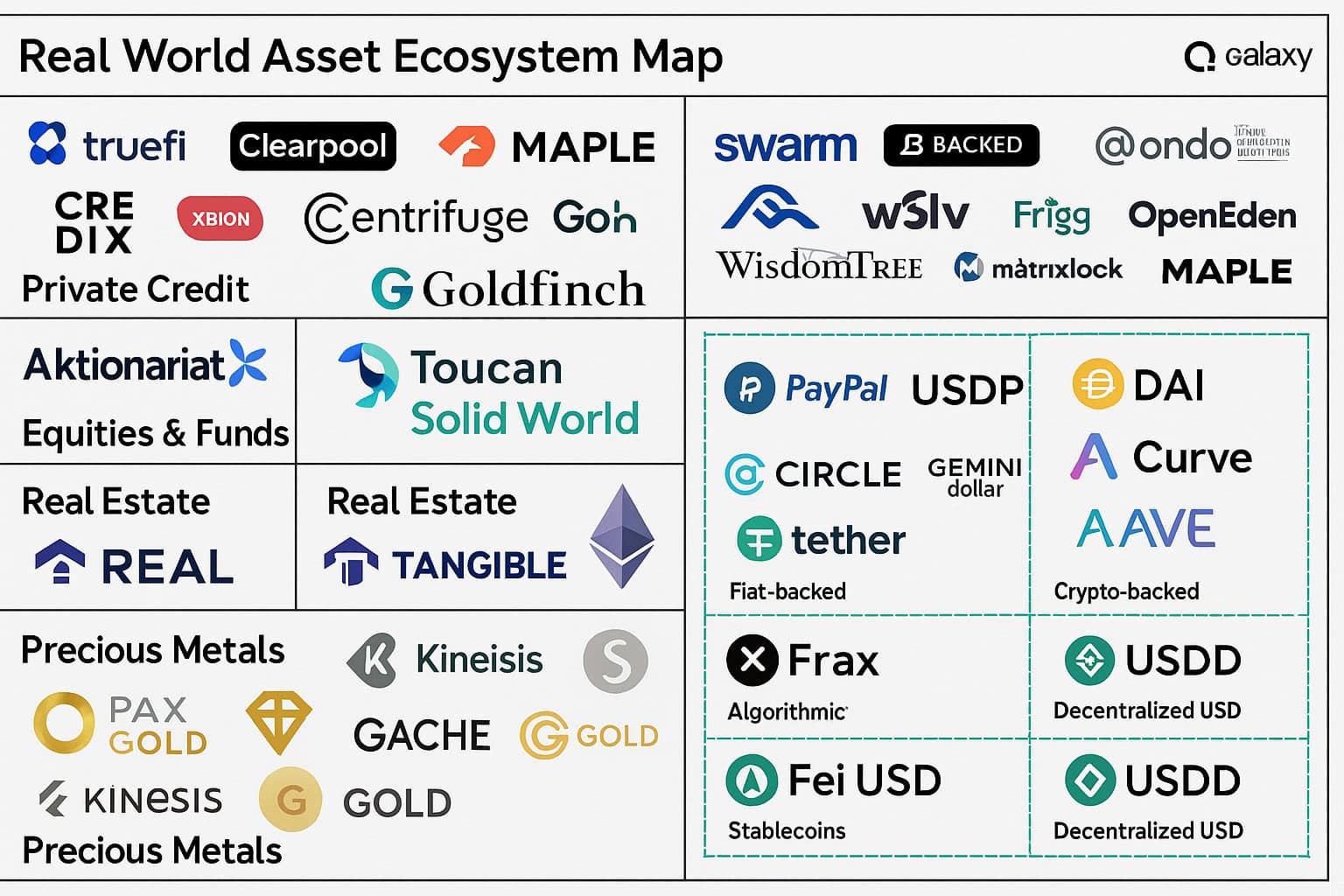

The ecosystem can be grouped into a few recognizable categories. Rather than trying to name every player, it is more useful to outline the market map and a few representative platforms.

Multi‑asset RWA and digital‑securities platforms

These platforms tokenize multiple asset classes, funds, credit, treasuries, and real estate, and often operate regulated trading venues, they define what is operationally feasible for sponsors without in‑house blockchain teams.

- Securitize

- SEC‑registered broker‑dealer, transfer agent, fund administrator and ATS operator.

- Tokenization partner for large managers including BlackRock; Securitize handles issuance and compliance for the BUIDL tokenized fund.

- DigiShares & DigiShares Capital

- White‑label tokenization and investor‑operations platform for real estate and other assets (primary issuance, KYC/AML, corporate actions, and secondary modules).

- Blocksquare

- Tokenization infrastructure is used by businesses in 29 countries, with more than US$200 million in tokenized real estate across dozens of properties.

Real‑estate‑focused investment platforms

These are more visible to investors and media, and often focus on residential or small commercial assets with low minimum tickets:

- RealT – tokenized U.S. properties with rental distributions; aims to “democratize access” to curated real estate.

- Lofty – fractional single‑family rentals, with a retail‑friendly UX and integrated secondary market.

- Reental – tokenized real estate investments across Spain, the U.S., Mexico and other markets, with more than €30M+ in assets tokenized and an expanding footprint in Latin America.

- Brickken – Infrastructure provider for token issuers. Focused on compliance, issuance, and investor dashboards, enabling sponsors to maintain direct control over branding and investor relationships.

- Bynarix – Targets commercial and development-stage assets. Emphasis on automated reporting, KYC onboarding, and flexible structures (equity and debt) to accommodate multiple investor profiles.

- RealtyMogul – A U.S. online marketplace that gives accredited investors access to private real estate deals, including commercial assets and private REITs. It focuses on curated opportunities, due-diligence transparency, and income generation through distributions.

- RealBlocks – A digital platform for private fund managers that streamlines fundraising, investor onboarding, and secondary trading of fund interests. It enables asset managers to offer tokenized real estate investments with improved liquidity and global investor access.

- Propy – A blockchain-driven real estate transaction platform focused on digital title recording, smart contract closings, and crypto-friendly purchase processes. It modernizes escrow and deed recording rather than purely enabling fractional investment.

A word on Regulations

The central regulatory theme worldwide is straightforward: putting a traditional security or property-linked claim on a blockchain does not change its legal nature. Tokenized securities are still securities.

Regulators have been explicit:

- The U.S. SEC’s digital asset framework and subsequent statements emphasize that digital tokens that function as investment contracts are subject to federal securities laws.

- Recent speeches and enforcement actions reiterate that tokenized stocks and other asset‑backed tokens must comply with the same registration, disclosure, and broker‑dealer rules as their off‑chain equivalents.

For real estate, that translates to:

- Tokenized equity or notes in an SPV are generally treated like traditional private placements or fund interests.

- Platforms must implement KYC/AML, keep accurate registers, and use licensed intermediaries where required.

Europe and MiCA

The EU’s Markets in Crypto‑Assets Regulation (MiCA), now in force, mainly targets crypto‑assets that are not already classified as traditional financial instruments (e.g., utility tokens and stablecoins). Tokenized securities typically remain governed by existing securities law, but MiCA still shapes how platforms and service providers are licensed.

Key takeaways for tokenized real estate:

- If the token qualifies as a transferable security or fund unit, the issuer must comply with the Prospectus Regulation and MiFID‑style rules.

- MiCA provides clarity for the platform layer (custody, trading venues, stablecoin usage), which reduces regulatory uncertainty for tokenized CRE structures.

Dubai / UAE: VARA’s RWA rulebook

Dubai’s Virtual Assets Regulatory Authority (VARA) has become a focal point for RWA tokenization:

- VARA’s 2025 rulebook explicitly addresses RWA tokenization and gives issuers and platforms a structured path to licensing and secondary trading.

This is one reason we see large tokenization announcements in the Gulf region: the legal runway is clearer than in many Western jurisdictions.

United States: SEC rules and exemptions

In the U.S.:

- Tokenized real estate offerings typically rely on Reg D, Reg S, or Reg A+ exemptions, combined with transfer restrictions coded into smart contracts.

- Trading of security tokens must happen on registered exchanges or ATSs, which is why platforms like Securitize obtained ATS licenses and transfer‑agent registrations.

Recent U.S. guidance has clarified some edge cases (e.g., meme coins vs. securities), but the core position for RWA is stable: if it walks like a security, the token is regulated as one.

Latin America snapshot

Regulation in Latin America is evolving quickly and unevenly:

- Brazil

- The real estate regulator COFECI issued Resolution 1.551 in 2025, creating the first specific rules for real‑estate tokenization and signaling alignment between real estate brokers, registries, and blockchain‑based structures.

- The securities regulator CVM runs a regulatory sandbox (Instrução CVM 626) where tokenized securities projects have completed full issuance–distribution–burn cycles under supervision.

- Mexico

- Tokenized real estate sits at the intersection of securities law and the Fintech Law (Ley para Regular las Instituciones de Tecnología Financiera), making public retail offerings difficult but leaving room for structured, exempt placements.

- Colombia

- There is no comprehensive tokenization statute yet, but market experimentation is active. Platforms like Expedit and SQMU illustrate how tokenization is being used as an alternative financing tool in a housing‑deficit environment.

For investors, a simple rule of thumb is useful: if a right is not clearly spelled out in the off-chain documents, do not assume the token provides it.

A case on Liquidity: Promise vs. Reality

A few data points frame the conversation:

- Deloitte projects more than US$4 trillion in tokenized real estate by 2035, versus less than US$300 billion in 2024, implying an annual growth rate above 25%.

- Europe alone represented roughly US$1.23 billion in tokenized real estate in 2024, about 23–24% of the global tokenization market.

- In the broader RWA space, the fastest growth and deepest liquidity are currently in tokenized treasuries and money‑market funds, where BlackRock’s BUIDL and similar products dominate issuance.

Real estate is therefore growing rapidly but still small compared to the global CRE universe and relative to more standardized RWAs like public‑market debt.

Where liquidity is today

In practice:

- Most on‑chain trading volume is in stablecoins and short‑duration fixed income (tokenized T‑bills and MMFs).

- Real‑estate tokens do trade, but:

- Often on niche or regulated platforms (Securitize ATS, RealT’s pools, Reental’s internal markets, etc.).

- Volumes are modest, and order books can be thin.

Tokenization does, however, can improve liquidity potential:

- Fractionalizing interests lowers minimum number of tickets.

- On‑chain settlement shortens trade and distribution cycles.

- Global investors can, in principle, participate in the same structure—subject to KYC and local law.

Design decisions that affect liquidity

For sponsors, three design levers matter:

- Investor base – a purely local, buy‑and‑hold investor base will not create much secondary liquidity, regardless of tokenization.

- Product simplicity – standardized income products (stabilized multifamily, core debt funds) are more likely to attract continuous interest than highly idiosyncratic development projects.

- Market‑making arrangements – engaging market‑makers or designing issuer‑run buy‑back programs can support liquidity, though they come with regulatory and capital implications.

Tokenization enables liquidity design; it does not manufacture demand.

For sponsors and developers

Beyond technology and regulation, tokenization changes how costs and benefits are distributed across the capital stack.

Tokenization can:

- Lower fundraising friction – digital onboarding, smaller tickets, and cross‑border reach can reduce time to close, especially for repeat issuers.

- Automate operations – distributions, statements, and cap table management can be partially or fully automated, reducing back‑office burden.

- Potentially lower cost of capital if new investor segments (e.g., global retail or crypto‑native yield seekers) accept lower required returns for access and liquidity.

But:

- Legal, structuring, and platform costs can be significant, especially for smaller deals.

- Sponsors must invest in investor education and governance, especially where tokens are sold to first‑time or cross‑border investors.

For investors

For investors, tokenization offers:

- Access – previously inaccessible strategies (e.g., institutional‑grade CRE or cross‑border portfolios) with low minimums.

- Operational benefits – faster settlement, digital records, and, where available, secondary trading.

- Composability – in some cases, tokens can be used in DeFi applications (collateral, lending) to create additional liquidity channels.

However, investors still bear:

- Property‑level risks (vacancy, cap rate movements, leverage).

- Regulatory risk (changes in how tokens are treated in each country).

- Technology risk (custody, smart‑contract bugs, platform failure).

Governance and Investor Protections

For sophisticated LPs and regulators, governance is where tokenization is often evaluated most closely.

Key issues to address in any tokenized CRE transaction:

- What rights does the token confer?

- Voting on major decisions? Information rights? Profit‑sharing only? Liquidation priority?

- How are rights enforced?

- SPV operating agreements and shareholder agreements must clearly tie on‑chain records to legally recognized ownership and decision‑making mechanisms.

- What happens in disputes or insolvency?

- Courts will primarily look at contracts and local law, with blockchain records serving as evidence rather than standalone sources of legal truth.

For investors, a simple rule of thumb is useful: if a right is not clearly spelled out in the off‑chain documents, don’t assume the token provides it.

Governance, Oracles, and Smart‑Contract Infrastructure

Tokenized CRE only works if three layers line up: legal governance, on‑chain governance, and data/automation infrastructure (oracles and smart contracts). If any of those fail, the token becomes, at best, a confusing wrapper around a traditional asset.

Governance frameworks: who decides what, and under which rules?

With tokenized RWAs, governance isn’t just “DAO vs. no DAO.” (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) It’s a layered framework that must reconcile:

- Corporate law (SPV, fund, trustee)

- Securities regulation (investor rights, disclosures)

- Smart‑contract logic (who can trigger what on‑chain)

A robust governance design for tokenized real estate typically considers:

a. Levels of governance

- Asset‑level governance: Decisions about leasing, capex, refinancing, sale, etc. These are usually taken by the sponsor/GP or asset manager under a traditional management agreement.

- Vehicle‑level governance (SPV/fund)

Investor rights over:

-

- Approving or rejecting major decisions (sale, recap, leverage limits)

- Replacing the manager in case of negligence or persistent underperformance

- Approving fee changes or amendments to key terms

- Token‑level governance

How votes and rights are expressed and enforced on‑chain:

-

- One‑token‑one‑vote vs. one‑investor‑one‑vote

- Quorum and majority thresholds

- How on‑chain votes trigger off‑chain legal actions (board resolutions, amendments, etc.)

b. Governance models in practice

Most tokenized CRE today uses hybrid governance, not fully decentralized DAOs.

- Manager‑centric with investor safeguards: Sponsor retains day‑to‑day control; investors have veto or consent rights for defined “reserved matters” (leverage caps, sale, change of control).

- Token‑holder voting on defined events: Smart contracts can tally token‑holder votes and produce a verifiable result, which the SPV is contractually bound to follow.

- Role‑based permissions: Different roles (issuer, admin, custodian, auditor) have precisely scoped on‑chain permissions, often enforced via multi‑sig wallets.

c. Key governance questions to document clearly

- Who can:

- Change the smart contract or upgrade the platform?

- Pause transfers (e.g., in case of regulatory or technical issues)?

- Replace asset managers or service providers?

- How are conflicts of interest handled (e.g., sponsor’s promote vs. early sale at a discount)?

- How are disputes resolved, local courts, arbitration, or both, and how do courts treat on‑chain records?

For investors and regulators, if a decision materially affects cash flow or rights, the process should be explicit in both legal docs and smart contracts.

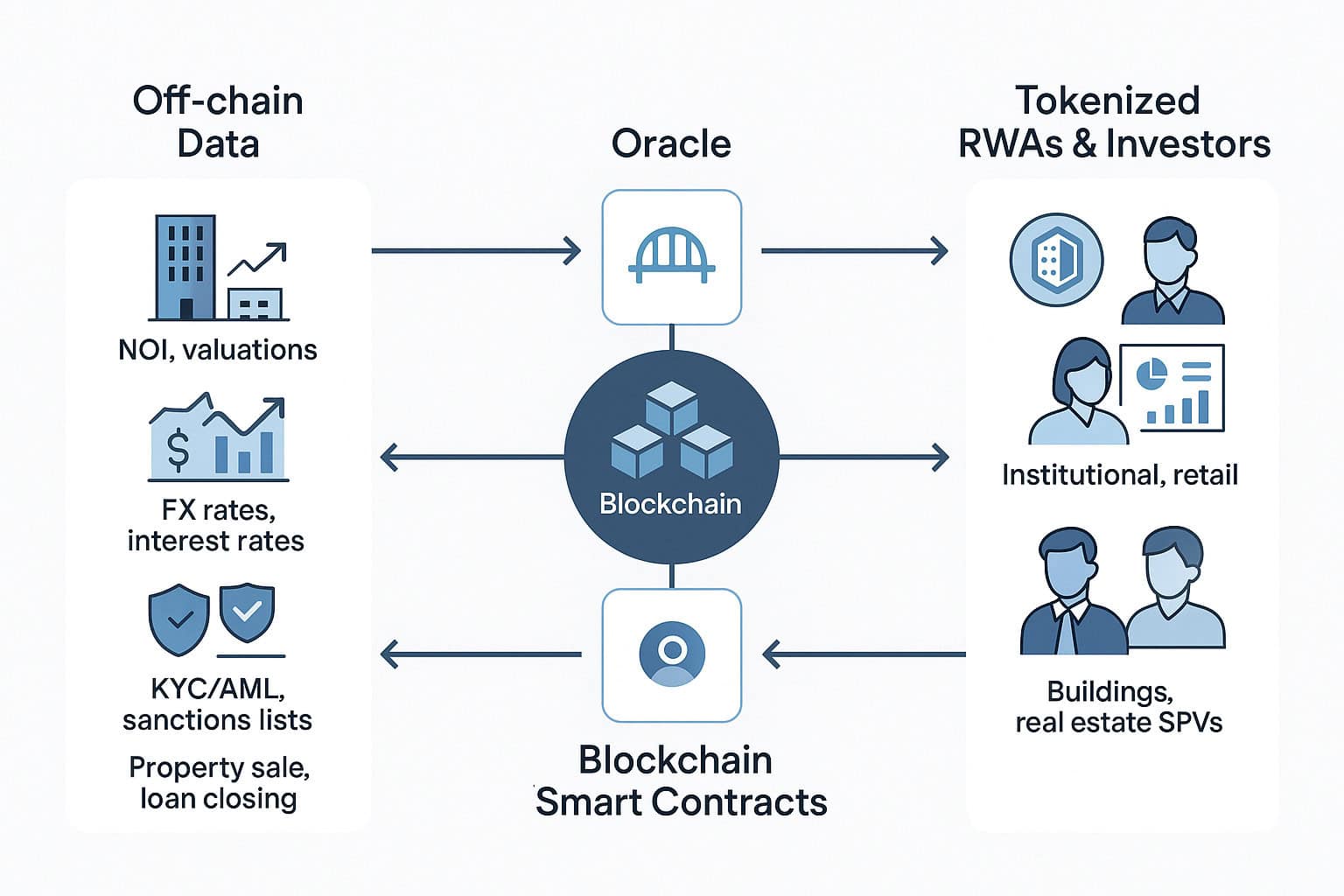

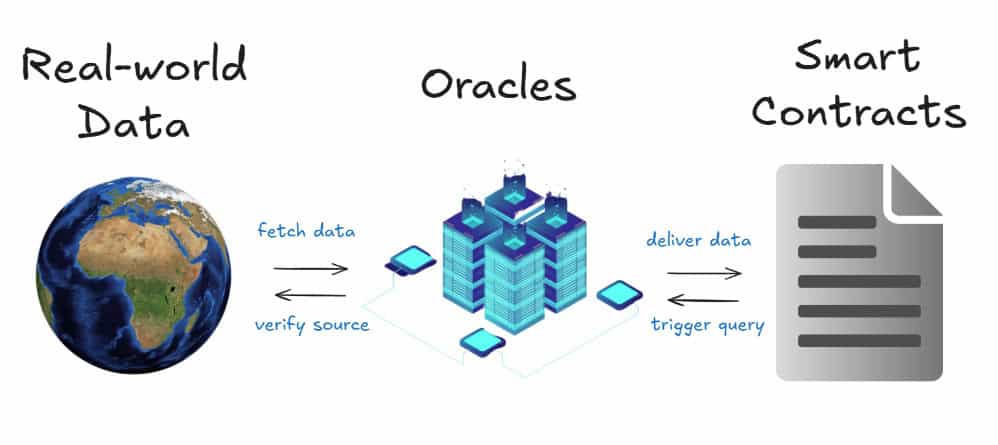

Oracles and smart contracts

Blockchains are closed systems. They cannot “see” rents, interest rates, FX rates, or transaction closings on their own. Oracles are the bridge: specialized services that feed trusted off‑chain data into on‑chain smart contracts, so those contracts can react automatically.

How oracles bridge off-chain data and smart contracts. Image source: Cyfrin -https://www.cyfrin.io/glossary/oracle

In tokenized CRE, oracles and smart contracts show up in at least four practical areas:

a. Cash‑flow and performance automation

- Rent and income feeds: Property‑management or accounting systems send net cash‑flow data (after expenses, debt service) to the oracle.

- Automated distributions: Smart contracts can read that data and calculate pro‑rata distributions to token holders, triggering payments in fiat‑backed stablecoins or other assets.

- Performance trigger: DSCR, occupancy or other pertinent metrics movements falling below a threshold can trigger:

- Notifications and covenant checks

- Restrictions on sponsor fees or distributions

- Requirement to submit a remediation plan

Here, oracle risk is non‑trivial: if the data feed is wrong or manipulated, payouts and covenant logic can misfire.

b. Price, FX, and interest‑rate data

Tokenized assets often depend on external financial data:

- Price and oracles: Appraisals, cap‑rates, or index movements may feed into periodic calculations used for reporting or for secondary‑market reference pricing.

- FX oracles: Critical when the asset is denominated in local currency, but tokens and distributions are in USD or stablecoins.

- Rate oracles: Benchmarks (SOFR, local reference rates) can inform floating debt tokens or preferred equity coupons.

In all these cases, the choice of oracle provider and fallback mechanism (e.g., manual override, median of multiple sources) is part of the risk profile. For real estate smart contracts, leading oracle providers like Chainlink, Pyth Network, API3, and Band Protocol supply crucial off-chain data such as property valuations, market trends, ownership records, and legal data, enabling decentralized apps (dApps) to execute functions like tokenization, DeFi lending, and automated property management by securely bridging real-world info to the blockchain.

c. Compliance and identity oracles

Many RWA platforms effectively use “oracles for identity and compliance”:

- KYC/AML providers attest on‑chain that a given wallet belongs to an eligible investor type (accredited, EU professional, etc.).

- Jurisdiction or residency checks can be embedded at the oracle level to block transfers to ineligible jurisdictions.

- Sanctions and watchlist updates can be reflected through oracle updates, enabling dynamic compliance without reissuing tokens.

This makes on‑chain transfer restrictions responsive to changing regulations and investor status, but it also introduces dependency on external compliance providers.

d. Event oracles for lifecycle milestones

Tokenized CRE structures often need reliable confirmation of discrete events:

- Closing of a property acquisition or sale

- Registration of a mortgage

- Completion of a construction milestone triggering drawdowns or earn‑outs

Event oracles can be implemented via:

- Trusted third‑party attestations (notary, title company, law firm)

- Platform‑admin or multi‑sig confirmations for specific events

- Integration with land‑registry APIs where available

Because these events are legally sensitive, most structures combine oracle inputs with explicit human validation and clear liability frameworks.

Practical Checklists

To end Part II, here is a concrete list of questions that can be use internally:

Checklist for sponsors and developers

Before committing to tokenization, ask:

- Asset suitability: Is this a stable, understandable asset (or portfolio) with clear cash‑flow dynamics?

- Investor base: Which jurisdictions are my investors in? Can I realistically comply with their securities regimes?

- Regulatory route: Which exemption or registration path will I use (Reg D/S, EU prospectus exemptions, local sandbox, etc.)?

- Platform and technology Will I use a white‑label platform (DigiShares, Blocksquare, etc.) or build in‑house?

- Liquidity plan Is secondary liquidity truly important for this deal? If yes, which regulated venue will we use and who, if anyone, will support market‑making?

- Governance and reporting: Are token‑holder rights, governance, and reporting standards clearly defined and realistically manageable?

10.2 Checklist for investors

Before buying a real‑estate token, ask:

- What exactly do I own? Equity, debt, revenue‑share or something else? How is it documented?

- Who is the issuer and under which law? SPV jurisdiction, platform licensing, and supervising regulators.

- Where and how can I exit? Is there a secondary market? Are there any lock‑ups and transfer restrictions?

- What are the major risks? Property risk (leasing, cap‑rates), leverage, regulatory risk, platform and smart‑contract risk.

These questions are deliberately simple; if the answers are vague, investors should proceed cautiously.

Conclusion: When Tokenization Actually Makes Sense for CRE

Tokenization does not magically solve fundamental commercial real‑estate challenges: underwriting remains hard, local regulations still matter, and good governance does not come out of a smart contract by default.

What it can do is:

- Expand who can invest in each strategy

- Improve the efficiency and transparency of capital formation and operations

In other words, tokenization is best understood as an infrastructure upgrade to the existing private‑markets model, not a speculative detour.

Frequently Asked Questions about Real Estate Tokenization: From Concept to Execution

What does it mean to tokenize real estate?

Tokenization is “a structuring and distribution strategy layered on top of the traditional property.” It allows claims on cash flows or asset value to be packaged as digital tokens representing equity, debt, or other rights in an SPV that owns the property.

How are tokenized real estate offerings structured legally?

Most tokenized real estate deals use a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to hold the asset. Tokens then represent interests in the SPV, such as shares, membership interests, or contractual rights. Legal structure and jurisdiction are determined by where the property and investors are located.

Are tokenized real estate assets regulated as securities?

Yes. If investors are passive and expect profits from a sponsor’s efforts, the tokens are treated as securities under laws like the U.S. SEC’s Howey test. Tokenized securities must follow applicable securities regulations, regardless of blockchain technology.

What types of investor rights can a real estate token include?

Tokens can represent equity, preferred equity, debt, or revenue-share interests. Rights may include profit-sharing, voting, or governance, but “if a right is not clearly spelled out in the off-chain documents, do not assume the token provides it.”

How is secondary market liquidity achieved for tokenized real estate?

Liquidity is possible but not guaranteed. Trading typically occurs on regulated platforms like ATSs (e.g., Securitize). Liquidity depends on investor demand, product simplicity, market-making support, and compliance with jurisdictional restrictions.

Which platforms support real estate tokenization today?

Examples include:

Securitize (full-stack issuance and trading)

DigiShares and Blocksquare (white-label tokenization platforms)

RealT, Lofty, and Reental (retail-focused property tokenization)

Brickken, Bynarix, and RealBlocks (infrastructure and fund tokenization)

What regulatory frameworks apply to tokenized real estate globally?

U.S.: Reg D, Reg S, and Reg A+ exemptions apply; tokenized securities must follow SEC rules.

EU: Existing securities law applies; MiCA clarifies platform and stablecoin oversight.

Dubai: VARA’s 2025 rulebook provides explicit RWA tokenization guidelines.

Latin America: Brazil’s COFECI and CVM have issued rules and sandbox programs; Mexico and Colombia are evolving.

How do smart contracts and oracles support tokenized real estate?

Smart contracts handle tasks like token issuance, automated distributions, and voting. Oracles supply off-chain data such as rents, FX rates, appraisals, and KYC status. These tools enable automation but rely on accurate and secure data feeds.

What governance models are used in tokenized real estate?

Most models are hybrid:

Manager-centric with investor consent on key matters (sale, leverage caps)

Token-holder voting via smart contracts for defined events

Role-based permissions enforced on-chain with clear governance tiers (asset, vehicle, token)

Clarity in legal and smart contract design is essential for enforceability.

What are the main benefits and risks of real estate tokenization for sponsors and investors?

For sponsors:

Benefits: Broader investor reach, automated operations, lower friction in fundraising

Risks: Legal complexity, investor education needs, regulatory exposure

For investors:

Benefits: Access to institutional real estate, potential liquidity, digital ownership

Risks: Property-level risk, regulatory risk, tech failures, unclear governance