All You Need to Know About Real Estate Gross-Ups

“Gross-up” clauses have caused confusion, and occasionally consternation, amongst tenants signing commercial leases for the first time. While many tenants are happy to pay for building services they use on a daily basis, many are riled when they pay inflated prices when a building is less than 100% occupied.

However, as this article will explain, gross-up provisions are fair mechanisms that protect both landlords and tenants from the cyclical volatility of the commercial real estate market. But what does a gross-up relate to specifically, and how do they work in practice?

Note from Spencer: This is a guest post shared by long-time A.CRE reader Douglas Kohn. Douglas is the Director of Investments at Exor Asset Management and Adjunct Professor of Real estate at Fordham University in New York, NY. A huge thank you to Douglas for sharing his knowledge!

Gross-up provisions are common to multi-tenant property types, where tenants are responsible for some share of operating costs.

What is a Gross-Up?

A gross-up clause specifically refers to the amount a tenant pays toward the variable portion of the operating expenses of a commercial building. Services such as cleaning, HVAC, water, and electricity are all examples of services that are variable, as their cost goes up and down directly in proportion to the number of tenants making use of them.

While tenants expect to pay landlords for the use of these services, they often underestimate how closely these expenses are linked to occupancy rates. For instance, if a building has plenty of vacancies, whole floors can remain in darkness, HVACs can be put on sleep mode, and water use will drastically fall.

A gross-up is the act of a landlord distributing those variable operating expenses to tenants on a pro-rata basis as if the building was at 95%-100% occupancy. In some instances, this takes place even if the building has only one tenant. This provision ensures that landlords do not end up making up the variable expense shortfall out of their pocket and protects the tenant from overpaying for their share.

At this point, it’s useful to look at a hypothetical example to understand how a gross-up clause works in practice.

Gross-Up Example

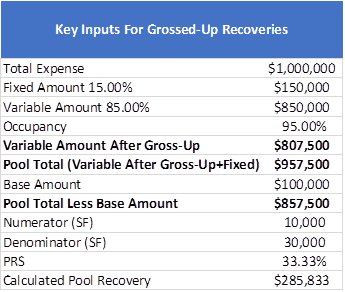

Let’s use the hypothetical example of a building that has $1,000,000 in expenses. 85% of those expenses are variable and 15% fixed. The building is 2/3 occupied (66.67%). The first step is to multiply the variable portion of the expenses ($850,000 * 66.67%) resulting in a subtotal of $566,667. Next, the fixed expenses of $150,000 are added to the subtotal bringing the total expense pool to $716,667. Now assume the expense reimbursement is has a base amount of $100,000. And the tenant has a 33.33% pro rata share. The recovery for that expense pool would be $205,000 (please see attached Excel example).

If this had just been a ‘normal’ reimbursement, the tenant would only need to worry about its pro rata share of expenses over a base year. If those are not adjusted, the variable amount being used for the expense pool could be substantially lower, resulting in a lower tenant reimbursement.

Another example is as follows:

In the hypothetical example of a 20-story building that has 20,000 square feet of leasable space on each floor, providing a total of 400,000 square feet. If the building were leased to 10 tenants whom each take an entire story, each tenant’s proportional share would come to 5% (one-twentieth).

When it comes to the landlord’s costs of running the building, let’s suppose that total expenditure comes to $250,000 per year. Of those costs, $200,000 (such as insurance and real estate taxes) is fixed, and the remaining $50,000 is variable. Without a gross-up provision, each tenant would pay fees of $12,500 made up of $10,000 fixed and $2,500 variable based on their 5% share.

In this scenario, the landlord would be left with a $25,000 shortfall to cover, since the tenants’ payments (10 x $2,500) would only account for half of the variable costs incurred by the landlord ($50,000). However, with a gross-up provision, a landlord charges a pro-rata share to each tenant based on a fully occupied building.

If the variable costs were $50,000 at 50% occupancy (as per the example), then one could objectively assume that a full building would incur $100,000 in variable expenses. By paying the 5% proportional share of the so-called “grossed-up” variable operating costs, tenants would part with $5,000 each as opposed to $2,500, covering the $50,000 costs incurred by the landlord.

In this scenario, the tenant may become frustrated by paying double the amount for variable expenses. However, the practice is not as unfair as it may seem.

For additional information about commercial real estate leases, review Michael’s post ‘Understanding Commercial Leases‘

Are Gross-Ups Fair?

Many tenants become irked by gross-up clauses when, in fact, they are a fair mechanism for recouping costs directly-related to tenant activity. Janitorial services, HVAC operation, lighting, and water supply, are all services that a tenant depends upon without providing any benefit to the landlord. Therefore, it can’t be considered fair that expenses incurred by required tenant services should fall upon the shoulders of a landlord, just because the building is not 100% occupied.

On the surface, a gross-up provision may look like a landlord protection mechanism; but in many instances, it protects the tenant too. Firstly, it provides budgetary certainty for the tenant. Leases without a gross-up provision may have volatile swings in variable expenses each year, reflecting the changing occupancy rates of the building.

Furthermore, in some instances, it can prevent tenants from overpaying for their variable expenses. Some commercial leases offer the tenant the opportunity to only pay for their proportionate variable costs during the base year of the agreement. If the building wasn’t fully occupied during that initial year and the building occupancy increases (driving up variable expenses), then the tenant will end up paying a share of the new tenants’ costs.

This allows the landlord to secure a windfall by effectively back-loading these variable expenses onto the original tenant, provided they have been reimbursed for those increased expenses under the lease terms of the new tenants. Therefore, tenants should insist on “grossing-up” payments at the very beginning of the lease and thereafter to protect themselves from overpaying.

It’s important to note that “grossing-up” should only take place on expenses that vary with tenant use. Fixed costs such as building insurance will be the same regardless of whether a building is full or empty. Therefore, those expenses shouldn’t be altered in this manner, because then the burden to fill vacant spaces would unduly shift from the landlord to the tenant.

Do Your Homework and Always Read the Fine Print

If you are likely to be entering a commercial lease shortly, it pays dividends to go through your contract with a fine toothcomb to unearth any unfair clauses. As mentioned, avoid agreements that look to gross-up fixed operating expenses. Furthermore, make sure to carefully check the terms of any base year deals as they may prove costly mistakes in the future.

If you do spot a gross-up clause, look at how they are going to be enforced. Some leases allow for landlords to allocate 100% of the variable expenses of a fully occupied building to just one tenant. It may be worth negotiating some maximum gross-up percentages to protect yourself in the rare scenario of being the only tenant. Conversely, if you do not see a gross-up clause, try and negotiate one with your prospective landlord to control your future costs.

Finally, do your homework on your landlord. Do they have a strong track record of filling their buildings? If they have eight other buildings in their portfolio and only 50% of them are more than half full, then you could end up consistently paying more than you use in terms of variable operating expenses. A landlord’s solid performance history allows you to go into the deal with a lot more confidence that your “grossed-up” fees will more fairly reflect your usage of those services.

Frequently Asked Questions about Real Estate Gross-Up Provisions

What is a gross-up provision in commercial real estate?

A gross-up provision allows a landlord to allocate variable operating expenses to tenants as if the building were at 95%-100% occupancy. This ensures that tenants pay a fair share for services like HVAC, electricity, and janitorial, even if the building isn’t fully occupied.

Why are gross-up clauses used in leases?

Gross-up clauses protect landlords from absorbing variable expenses when occupancy is low and provide tenants with more consistent budgeting. They also prevent tenants from overpaying if base year expenses were calculated during a low-occupancy period.

What expenses can be grossed up?

Only variable expenses—those that fluctuate based on building usage—should be grossed up. These include janitorial services, HVAC, lighting, and water. Fixed costs like insurance or property taxes should not be grossed up.

How does a gross-up affect what a tenant pays?

A gross-up can increase a tenant’s reimbursement amount during periods of low occupancy by estimating variable expenses as if the building were fully occupied. This avoids under-collection of costs that are directly tied to tenant usage.

Can gross-up clauses be unfair to tenants?

While they may seem unfavorable at first, gross-up clauses can actually benefit tenants by offering budgeting stability and avoiding future overpayments tied to rising occupancy. They become unfair only if used to gross up fixed expenses or applied excessively.

What should I look for in a lease regarding gross-ups?

Tenants should ensure that only variable expenses are subject to gross-up, confirm how occupancy assumptions are calculated, and consider negotiating a cap on the maximum gross-up percentage. It’s also wise to evaluate the landlord’s historical occupancy performance.

How can gross-up clauses protect tenants?

They provide cost predictability and prevent tenants from subsidizing future occupants. For instance, if base year expenses were low due to vacancies, grossing-up ensures future increases aren’t unfairly shifted to early tenants.

Should gross-ups apply in single-tenant buildings?

Gross-up provisions can still apply even in single-tenant buildings to ensure consistency in how variable expenses are treated, though their application may be limited depending on lease structure and negotiation.