Deep Dive – Land Acquisition and Assemblage (Updated September 2024)

This is a topic I’m all too familiar with. You see, I cut my teeth in real estate largely sourcing and negotiating residential and mixed-use land acquisition opportunities. I’ve put land deals together both as a fiduciary and as a principal, both in the United States and abroad. In this deep dive on land acquisition and assemblage, I’ll share my thoughts on how to be a successful “land pro”. I’ll also share a Ben Stevens Skyline Forum interview with an expert in this area, and get that perspective on the topic.

First let me start by saying, land acquisition is tough! It demands a level of grit, patience, risk taking, and vision that most of us don’t have. As a result, much of the value in a ground-up development deal is in the land acquisition and entitlement phase. So those who are good at it make a lot of money doing it.

In my experience, success in land acquisition ultimately comes down to mastering (or naturally possessing) three qualities: persistence, vision, and emotional intelligence.

You might find our Excel pro formas for analyzing land investments useful.

A Word on Terminology – Land Acquisition and Land Assemblage

First a distinction between land acquisition and land assemblage. Land acquisition refers to the process of acquiring land for real estate purposes. This may include acquiring just one parcel or many. I include in land acquisition the process of securing entitlements (zoning and land use rights), since without the proper entitlements the land strategy is worthless.

When I refer to land assemblage, I’m referring to a tactic sometimes employed by land acquisition professionals to bundle multiple properties into one.

From our A.CRE Glossary of CRE terms:

Land Assemblage: A tactic employed in land acquisition, where a real estate professional acquires two or more adjacent parcels, combining them into one. Land assemblage can be a time-consuming, complicated process – with the complexity increasing exponentially depending on the number of parcels and land owners. However, the complex process is worth it when the value of the whole (the combined parcels) is greater than the sum of the value of the parts (the individual parcels).

An example of land assemblage, would be a real estate developer purchasing an entire block of homes, each from a different owner. Once the entire block is acquired, the developer tears down the homes to build a shopping center. Thus, the value of the sum of the individual parcels is less than the value of the combined (assembled) parcel.

The value of the whole (the combined parcels) is greater than the sum of the value of the parts (the individual parcels).

Persistence – The Key Ingredient

Talk to any land acquisition professional, and they’ll likely tell you that persistence is the key ingredient to success in land acquisition. Sure, other aspects are important, but without a determination to overcome (innumerable) obstacles and see the process through, you will fail.

“It’s not that I’m so smart, it’s just that I stay with problems longer.” – Albert Einstein

The land acquisition process is fraught with rejection, false starts, and unexpected problems. It’s common to be optimistic about a parcel’s prospects one day, only for the deal to die the next. That’s because there are so many pieces that must fall into place for a deal to come together. Thus, land deals get done because the stakeholders stick with it.

A Personal Story About Persistence in Land Acquisition

Ben Steven’s guest in the interview below will further drive this point home, but let me share a personal experience that helps illustrate one element of persistence in land acquisition. It’s also an introduction to a part of my career you may be less familiar with.

I started my career as a real estate broker sourcing land for residential land developers. From the time I was a teen, I’d dreamed of being a residential land developer and so when I entered the business, I figured brokerage was a great way to learn.

I keenly remember the day, as an early 20-something new hire, going into my Principal Broker’s office and telling him that I wanted to source residential land.

You see, I’d called a family friend and boutique local residential developer that morning offering my services. In response, he told me if I could find land for him that he’d give me a piece of the deal. Not knowing entirely what that entailed, but filled with excitement and optimism, I headed straight to my boss’ office to get his advice.

His response has stuck with me to this day. After hearing about the opportunity and seeing my naive excitement, he flatly said, “finding residential land is impossible in this environment – it’s really a fools errand.”

I didn’t realize it at the time (pre-2007 in the United States), but finding land for residential lot development was nearly impossible. Most of the good plots were either tied up, held by families determined not to sell, or controlled by owners with unrealistic price expectations. Land owners were approached literally every week by developers seeking to purchase their land.

And so as a young guy getting my start in real estate, with few contacts and even less experience, I did what any young 20-something would do in this situation. I ignored my boss and charged ahead anyway!

I was hungry, determined, and had a chip on my shoulder. This helped me stick with it and forced me to think outside the box. I researched ownership on virtually every property in my target markets, cold knocked on countless farmers’ doors, sent hundreds of personal letters to land owners, and made who knows how many calls with near constant of rejection. In short, I pounded the pavement harder than the next guy, hoping it would be enough.

And it worked.

I eventually tied up my first parcel, then my second, then my third, and I was off. The constant sourcing and networking led me to new clients and new opportunities.

I can confidently say that my upward career trajectory in real estate, is largely due to that early persistence in land acquisition; a persistence ironically fueled by a boss who told me it was impossible.

Vision and the Entrepreneurial Mindset

Another quality that defines a successful land acquisition professional is vision. The professional must be able to identify what is possible with an otherwise vacant piece of land, and visualize how value can be added to that land. This involves creative thinking and a penchant for risk taking.

What I call vision, in this context, could likewise be called an entrepreneurial mindset. Some people naturally possess it, while others have to work to develop it. At its core, it’s about recognizing a need or dislocation in the market, and then seeking out ways to fill that need or remedy that dislocation.

Where Vision Comes In

In land acquisition, this vision most often is expressed as either:

- Land first, vision second or

- Vision first, land second

Land first, vision second is when you (the land acquisition professional) already have control of a piece of land. Perhaps you inherited the land, or your company has owned/controlled it for a long time. Perhaps it’s being used for a completely different use, and you’re exploring a higher and better use. Whatever the means by which you came to control the land, vision in these situations comes second.

Your job in a land first, vision second scenario is to dream up a use for the land that will maximize its value within the legal and physical constraints overlaying the land. Land first, vision second tends to be easier because you’re not likely pressured to close before executing on your vision.

Vision first, land second is exactly the opposite. You’ve likely identified an opportunity, developed a strategy, and now are seeking out land to bring about that vision. This scenario is far riskier than the first, since you don’t control the land at the outset, let alone know the price of the land! That big unknown – not having the land tied up – is one of the biggest impediments to raising capital and executing your strategy.

A Personal Example of Vision First, Land Second

Let’s return to my story, as it also illustrates well the creativity and vision often required in land acquisition.

Among all of my calls, letters, and door knocks to land owners, one particular call was made to the owner of a 250-acre defunct peach tree orchard. The property sat just outside city limits, and was zoned for agricultural use (one unit per 40 acres = max 6 units). The parcel sloped from north to south, with incredible views of an adjacent lake.

Peach production had been abandoned some years previous, and so the property was covered with overgrown peach trees. In talking to the land owner, he told me the orchard had been abandoned because the trees were no longer productive. The soils were especially rocky, and the orchard had never been especially productive. But as operating expenses rose, and the trees became older, it had become unprofitable to operate the orchard.

Our peach tree property acquisition was a home run. Unfortunately, the only relevant image I could find for this post was of an apple orchard!

The issue, per the farmer, was that the land could not be developed due to its agricultural zone. But neither could it be worked, due to the poor economics. And so it sat idle – something the local taxing authority wasn’t especially thrilled about.

I took the opportunity back to my client (my only client at the time!), who also happened to be a former city planner. He told me about a little known provision in the zoning law, that allowed for the land owner to seek a conditional use permit for one unit per two acres (one unit per 2 acres = 125 units) in an agricultural zone.

The big caveat to this route was, in order to secure this conditional use permit, the land owner had to demonstrate a compelling reason why the agricultural use was unnecessary and the new use would better serve the area.

My client felt, given the poor economics of the peach grove, that he could win the votes to secure the conditional use permit. So he put the property under contract at a price typical of agricultural properties ($6,000/acre).

Nine months and a lot of work later, he had obtained the conditional use permit. And three months later, he opted to sell the land, now entitled for 125 units rather than 6, for $22,000/unit.

Thus, vision first, land second – with a willingness to take a risk.

Emotional Intelligence and the Land Negotiation

Negotiating a land deal is about a lot more than money, especially if you’re dealing with a long-time owner-family. Whether you successfully convince the land owner to sell, comes down to a number of factors:

- Does the land owner like you and trust you?

- Does the land owner feel you can relate to him/her/them?

- What are your intentions for the land and are they consistent with the vision and values of the land owner?

- Where will the land owner live after the sale?

- How will the sale impact the land owner’s local reputation?

- If the land owner is a farmer, what will happen to the farm business?

- In the case of a family, how will the proceeds be split?

Emotional intelligence is especially important to land negotiations.

It’s amazing how seemingly little things, can blow up a land deal. I remember a deal, a five acre infill parcel with a small old owner-occupied home on it, that we negotiated for over a year. Twice, we had a verbally agreed upon LOI, only for the elderly owners (we’ll call them Dean and Joan – not their real names) to change their minds before signing it.

Eventually, we gave up. On our last call with the owner, we asked Dean (Joan was not on the call): “Dean, what happened? Why couldn’t we get this done.”

We figured he’d answer that we couldn’t pay him what his place was worth, since in the past that had always been their reason for stalling the process. But no.

With the deal dead, and I guess feeling like he could finally be honest with us, he said: “Well, actually guys. Joan is embarrassed to live in a subdivision, and we can’t afford more land in this area.”

Had we had more emotional intelligence or perhaps had we focused more on the wife than the husband, we might have gotten that deal done. Or if nothing else, we might have saved a year’s worth of our time.

Interestingly enough, I drove by that piece of land this past summer, and Dean and Joan still live there. Their estate will likely be the eventually sellers of that five acre parcel.

Our interview below expands on many of the points above, and offers some additional insights into the importance of emotional intelligence in negotiating land deals.

Analysis in Land Acquisition

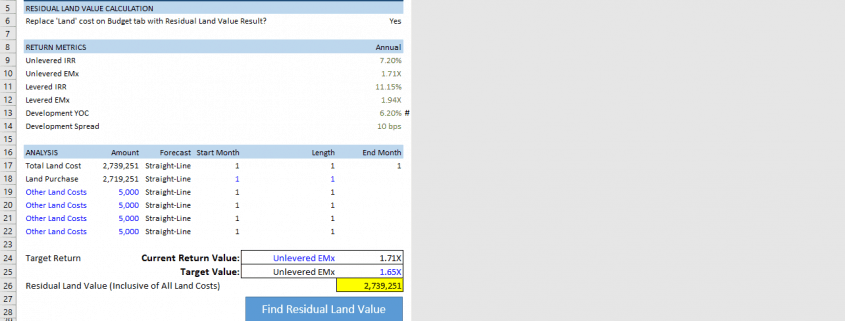

A blog post on Adventures in CRE isn’t complete without some discussion of real estate financial modeling. Assessing value for a land deal most often comes down to a residual land value calculation. Or in other words, what you can pay for the land comes down to what you can do with that land.

I won’t go in depth on residual land value here, since I’ve already written extensively on the subject. Instead, if this is a topic you want to understand further, I’ll point you to our post on calculating residual land value in Excel.

In terms of other tools for analyzing land transactions, you might find these models from our library of Excel models valuable:

- Residential Land Development Pro Forma – an Excel model for single phase residential lot development projects

- All-in-One Model with Residual Land Value Module– our Ai1 model now includes a residual land value module. With that module, you’re able to model out your project and then solve for a land price based on some target return assumption

Interview with an Expert in Land Acquisition – The Skyline Forum

To help illustrate what its like to be in the business of acquiring land, we’ve collaborated with a friend and fellow real estate aficionado, Ben Stevens. Ben is a project manager for a real estate development firm in Chicago. He graduated with an MBA in Real Estate and Urban Land Economics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. On the side, Ben hosts the The Skyline Forum, an online interview series with developers, architects, urban planners, and other real estate professionals.

In a recent episode of The Skyline Forum, Episode 16: Ten Thousand Acres, Ben interviewed Mike Mooney, Chairman of MLG Capital and co-founder of MLG Companies. Mike has spent decades acquiring land and land assemblages. In all, Mike has sourced over 10,000 acres in developing 19 business parks and 43 residential subdivisions.

Ben has graciously given us permission to share the interview. We’ve added a written transcript of the video, for those who prefer to read rather than listen/watch. Ben’s interview with Mike Mooney does an excellent job of giving you a glimpse into the world of land acquisition.

Read the Transcript of Ben’s Interview with Mike Mooney

10,000 Acres (00:00 – 0:59)

Mike Mooney: I’ve been involved in a lot of land dealings, probably 10,000 acres or more. About 7,000 acres of it has been in Wisconsin as part of our MLG capital operations. About half of that was the development of 19 business parks and about half development of 43 subdivisions.

In addition to that, I was retained in the mid-’70s to assist Champion International to assemble four square miles of land in the upper peninsula because they were about to buy 400 and some thousand acres of timber, and wanted to build a billion dollar paper and pulp mill.

And before that, I was an aspiring developer in the Republic of Ireland and I assembled 555 acres on the Shannon river in County Claire. Overall, that’s about 10,000 acres.

The Human Element of Land Acquisition (0:59 – 2:43)

Mike Mooney: If I get thinking back to the first one, I found a site in Ireland that would be suitable for a development I was aspiring to do, and I hired lawyers to front my efforts, because if Irish farmers found out that there were Americans trying to buy their properties, the price would just shoot out of sight.

We acquired about 200 acres, and when we came to the next parcel, which was the largest, it was 260 acres, the owner was a widow. Her husband had left her the property, and left some vested rights in the ownership to his sister.

This widow wanted to sell and the sister didn’t, but she had sign-off approval. And then the widow was also sharp enough to insist that she didn’t want to deal with the lawyers, she wanted to deal with whoever the buyer was. That meant we had to expose the fact that this was an American source of money.

I went over one day to meet with the two of them in their little farmhouse. I walked into the house, and it had dirt floors. It was furnished like a regular house, but the floors were dirt, so you can imagine the dampness. No wonder the husband was dead.

It was a real strange tense environment. The widow had me sit at the end of the table, and she sat on one side, her sister-in-law sat on the other side. And the reason for this was, they don’t talk to each other.

They live in this tiny little house, and they don’t talk to each other. If the widow said something to me, even though the sister was probably three or four feet away, I had to repeat what the widow said for the sister and vice versa.

Ben Stevens: This was assemblage and family therapy, all in one.

Mike Mooney: No kidding! Anyway, ultimately, we were able to acquire the property.

The Trick to Land Acquisition – Building Trust (2:43 – 6:09)

Ben Stevens: This raises a myriad of different questions, but I suppose the central one is, is there a trick to this? Could somebody legitimately write a book on how land assemblages are to be done? Or is every single one a different dirt floor, and a different two sisters that won’t talk to each other, in your experience?

Mike Mooney: Well, they’re all different. But there are some similarities. The similarities are there are humans involved. And humans have, generally, similar fundamental perspectives, and one is, they don’t want to be scared. They want to trust. And if they don’t trust, nothing works.

Of all of the tactics that I would use in doing that, they would all come down to being trustable. I’ll give you an example.

The biggest assembly I did, the four square miles just east of Iron Mountain, Michigan, and I had to assemble 33 parcels to make up this 2400 acres of contiguous land on the Niagara River, which was going to be a source of water for the paper and pump mill.

The first property was a gravel quarry, and the quarry owner lived on the property. I’d met other quarry operators since, and they’re pretty universally a bunch of tough guys.

I called in from Milwaukee, and set up an appointment for Saturday afternoon at 2:00. I pulled into his gravel driveway, and when I got close to the house, the driveway ended about 100 feet short of the house.

I grabbed my briefcase and I opened the door, and this booming voice says, “Stop where you are.”

I look out over there, there’s the guy I’m supposed to meet. He had a rifle across his chest, and I said, “Oh.”

I tried to casually dismiss this. I said, “Oh, I’m Mike Mooney. I’m the guy you talked to”, and I took another step forward.

“Don’t take another step.” He says to me, “What do you want?”

I was supposed to negotiate the acquisition of his house from 100 feet away, at gunpoint. It was clear the man was consumed with mistrust, so I said, “Do you have a lawyer?”

And he said, “Yes.”

I said, “Fine. How about if you give me the name of your lawyer, or if you call him, and we’ll set up a meeting at your lawyer’s office?” Because I figured that would be the only way I would get to be at the same table with this guy.

Now, being with his lawyer would complicate it, but that’s okay, I can handle that. And then I went into Iron Mountain, and went to a work man’s clothing store, and I bought Pendleton shirts and blue jeans and work boots.

It took me two years to assemble all of these parcels, and I would go up on weekends and take off my dress clothes, and I’d put on my work boots and my blue jeans, and I would go down and sit in people’s houses.

We were able to get his property, but the 33 properties consisted of the Kiwanis Christmas Tree Farm, a brand new subdivision, which the first house was going in, a horse ranch, a number of properties where people had lived for three or four generations.

In one house, I’m sitting at this table with this woman who says, “I’m fourth generation.” She said, “I was born on this table.”

Ben Stevens: You can take the table with you. I’m not trying to assemble the table.

Mike Mooney: Right!

Land Negotiation – Who Has the Upper Hand? (6:09 – 7:30)

Ben Stevens: Even with trust, as a transaction gets more and more progressed, people understand what the stakes are for Mike Mooney in this. And at a certain point, the cost basis doesn’t work anymore, so was it a matter of patience?

Could you just still make the numbers work because of the budget that was given to you? If the price is right, I’m sure you can assemble lots of things, but how did you keep the business end of it tied down enough that the deal would still work?

Mike Mooney: Well, when you think about the number of owners in that situation, every kind of emotion possible. One of the less likely occurrences is sophisticated greed.

Greed was there, but not sophisticated like the New York City guy. Especially in farm country like this, the biggest barrier was their emotional attachment to the property.

In the first couple properties, I realized I wasn’t making much progress because I was trying to neutralize their emotional concern. And all that did was anchor it in concrete.

I recognized that I had to get these concerns out of their head and out of their mouth, and it was easier for them to let go of them, than if it was still locked up in their brain. That eased the barriers between me and getting a contract.

Land Acquisition and Assemblage – The Process (7:30 – 10:00)

Ben Stevens: Walk me through the process that you would undergo with your current company if you wanted to assemble a city block downtown in Milwaukee.

Mike Mooney: Well, first of all, I’d have to start when I was a lot younger!

Ben Stevens: Right. Because of the time, the time horizon.

Mike Mooney: You just really need to know your sellers to the maximum degree possible.

Some of the properties we’ve been able to either acquire or sell, it was because we knew enough about either the buyer or the seller to know that they had to do [inaudible], which they wouldn’t have ever estimated that we could have known this, but we did, and that gave us a big lever and doing the negotiations.

We would do lots of research. We wanted to learn about were they experts in property ownership, or did … Sometimes people inherit stuff. Who are their lawyers? Are these guys deal makers or deal breakers?

And if an assemblage was required, one of the things we would do is our due diligence with regard to the level of sanity in the local government. Do they have a history … And there isn’t a lot of that, by the way.

We would try to get a handle on their history of dealing with economic development opportunities and their vision and wisdom and aggressiveness in pursuing that. And if we thought it was a welcome environment, we’d be more likely to do that.

In Beloit, we assembled 850 acres to do a project called The Gateway Business Park. I was very convinced that the city was going to jump on the bandwagon and help get this done.

From the time I went into the city hall the first time, to the time we turned the first spade of dirt, it was seven years. One key element for somebody who wants to do assemblages, is patience.

We would want to know all of that before we even decided to go ahead with that city block. And we would only decide to go ahead if we thought the odds were good enough that we could assemble the whole thing.

It would also be helpful if we could see that this company, with this LLC, owned this building, but under another name they owned this one over here, and this one over here, and we could get three in one set of negotiations.

Environmental Challenges (10:00 – End)

Ben Stevens: Another thing that’s kind of akin in some senses to assemblage is demoing or getting a contaminated site. They’re all kind of a family of acquisitions under the rubric by any means necessary. Doesn’t look like there’s a deal here, but there is. We’re going to either put it together, or we’re going to tear it down to get it, or we’re going to fix the contamination.

Did your penchant for assemblages lead you to do much of that, as well, just because it’s kind of a similar mentality? Or were there reasons that you just said, “No thanks. No demo work for us”?

Mike Mooney: Well, the irony is that this table I’m sitting at is where the Wisconsin’s legislation easing the ability to do, based upon bad soils or contamination, or whatever … And a bunch of lawyers and I sat around this table and drafted the guts of the legislation, and then somebody went up to Madison and got it passed.

The irony is that I took the lead in spending about eight months doing that, but since then, we’ve absolutely done none, because the rest of my partners are uncomfortable getting involved in contaminated properties.

For the most part, my experience is that the people who do that, are people that often came out of the soil remediation business.

Ben Stevens: They know it very well.

Mike Mooney: It’s a known quantity to them, and if they had built up enough financial resources, they could take that risk because, to them, it was less of a risk than it was for novices like us, with regard to how to handle the soil remediation.

Create Your Own Case Study

After following along with this land acquisition and assemblage deep dive, you can try your hand at your own practice test by using our Real Estate Case Study Creator GPT. This advanced tool generates comprehensive real estate case studies and custom modeling tests, allowing you to practice and refine your skills in a real-world context. Enhance your proficiency, build confidence, and ensure you’re interview-ready with tailored scenarios and tests that mimic the challenges you’ll face in the industry.

Conclusion on Land Acquisition and Assemblage

I hope you’ve enjoyed this Deep Dive as much as I have. Land acquisition is an exciting, scary, and (occasionally) lucrative field within real estate. It’s certainly not for everyone, but those who master the skills necessary to succeed, are handsomely rewarded.

And of course, another big thank you to Ben Stevens for his insightful interview with Mike Mooney. I highly recommend you check out Ben’s The Skyline Forum series.

Frequently Asked Questions about Land Acquisition and Assemblage

What’s the difference between land acquisition and land assemblage?

Land acquisition is the process of acquiring land for real estate purposes, including entitlements. Land assemblage is a specific tactic where multiple adjacent parcels are combined into one. “The value of the whole (the combined parcels) is greater than the sum of the value of the parts (the individual parcels).”

What qualities are critical for success in land acquisition?

Success in land acquisition requires persistence, vision, and emotional intelligence. The post emphasizes, “Persistence is the key ingredient,” while vision involves identifying potential and emotional intelligence helps navigate seller relationships.

Can you give an example of a “vision first, land second” strategy?

Yes. The post details a story where a defunct peach orchard zoned for agriculture was rezoned using a conditional use permit strategy. The result was a sale price increase from $6,000/acre to $22,000/unit after entitlements were secured.

Why is emotional intelligence important in land negotiations?

Land sales often involve long-time or multi-generational owners. Success depends on trust, empathy, and understanding motivations beyond money. “It’s amazing how seemingly little things can blow up a land deal,” as seen in the story of Dean and Joan.

What insights does Mike Mooney share about land assemblage?

Mooney stresses the human side of assemblage: “They want to trust. And if they don’t trust, nothing works.” His strategies included building rapport, dressing to blend in, and negotiating face-to-face—even under high tension like being held at gunpoint.

What is a residual land value calculation and why is it important?

Residual land value helps determine what a buyer can pay for land based on what can be built and earned on it. “What you can pay for the land comes down to what you can do with that land.” A.CRE’s Ai1 Model includes this functionality.

What tools and models are available to support land analysis?

Tools include:

Residential Land Development Pro Forma

All-in-One (Ai1) Model with Residual Land Value Module

Real Estate Case Study Creator GPT for generating realistic practice scenarios

How long can the land assemblage process take?

It varies greatly. One example shared took seven years from initial contact to dirt being turned. “One key element for somebody who wants to do assemblages is patience.”

What role do local governments play in land assemblage success?

A cooperative and visionary local government increases the odds of success. “We would do lots of research… and only decide to go ahead if we thought the odds were good enough that we could assemble the whole thing.”

Does the author recommend pursuing environmental remediation sites?

No. Despite drafting related legislation, the author and his team have avoided contaminated sites. “We’ve absolutely done none, because the rest of my partners are uncomfortable getting involved in contaminated properties.”